Crossing the frontier near Charleroi before dawn on 15 June, the French rapidly overran Coalition outposts, securing Napoleon's "central position" between Wellington's and Blücher's armies. He hoped this would prevent them from combining, and he would be able to destroy first the Prussian's army, then Wellington's.

Ney's orders were to secure the crossroads of Quatre Bras, so that he could later swing east and reinforce Napoleon if necessary. Ney found the crossroads of Quatre Bras lightly held by the Prince of Orange, who repelled Ney's initial attacks but was gradually driven back by overwhelming numbers of French troops.

Meanwhile, on 16 June, Napoleon attacked and defeated Blücher's Prussians at the Battle of Ligny using part of the reserve and the right wing of his army. The Prussian centre gave way under heavy French assaults, but the flanks held their ground. The Prussian retreat from Ligny went uninterrupted and seemingly unnoticed by the French.

With the Prussian retreat from Ligny, Wellington's position at Quatre Bras was untenable. The next day he withdrew northwards, to a defensive position he had reconnoitred the previous year—the low ridge of Mont-Saint-Jean, south of the village of Waterloo and the Sonian Forest.

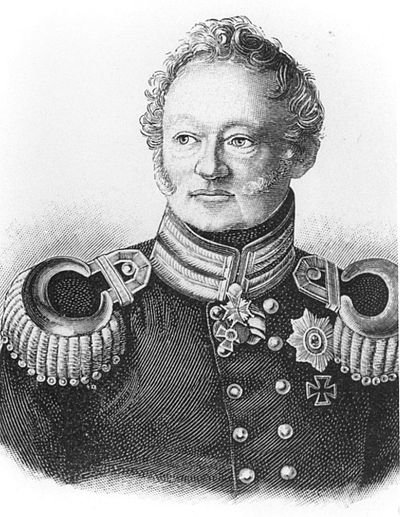

Before leaving Ligny, Napoleon had ordered Grouchy, who commanded the right wing, to follow up the retreating Prussians with 33,000 men. A late start, uncertainty about the direction the Prussians had taken, and the vagueness of the orders given to him, meant that Grouchy was too late to prevent the Prussian army reaching Wavre, from where it could march to support Wellington.